We just finished up a unit on dementia in my class on cross-cultural aging, and I realized that I had never really thought of it before– I had never really even known what dementia was before.

If I had had to describe dementia before this class, I probably would have just said it’s “when old people go crazy.” I didn’t even know it mainly has to do with memory loss.

For those of you wondering, this is the definition according to Google:

“A chronic or persistent disorder of the mental processes caused by brain disease or injury and marked by memory disorders, personality changes, and impaired reasoning.”

I’ve gotten into the whole googling-things-to-see-what-comes-up as a starting point for seeing how we understand certain concepts. So, just like I googled “old people” not too long ago, I decided to google-image dementia. This is what came up:

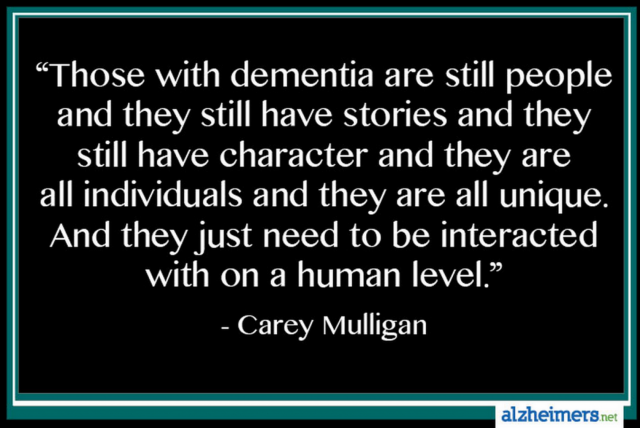

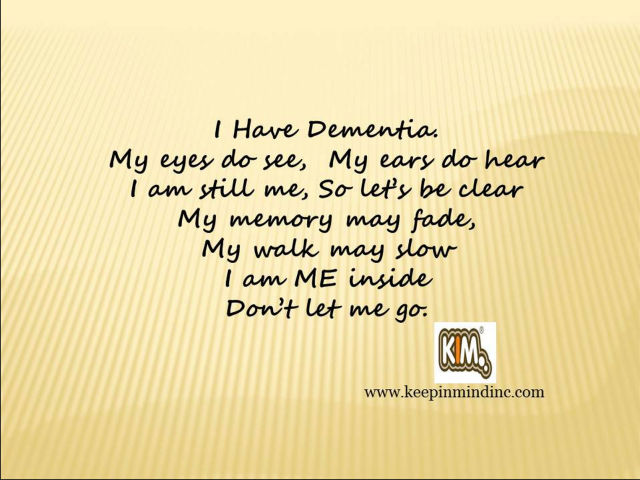

What I found especially compelling and saddening were the “quote” images that appeared first:

A lot of people fear dementia and Alzheimer’s disease– even my mom, at the age of 57, talks about her fear of it sometimes. My friend’s grandmother has it and she talks about how hard it is for her grandmother, how her grandmother knows she can’t remember things and it scares and frustrates her, how her grandmother lost her independence because of her dementia and how that was really hard for her.

But perhaps the fear surrounding dementia doesn’t have to do with forgetting things, but rather the negative social consequences that come with this forgetfulness.

In class we read a piece titled “On Recognition, Caring, and Dementia,” by anthropologist Janelle S. Taylor, in which she criticizes the stereotypes and stigmas around dementia and puts the disorder in a more positive light. Her own mother has dementia, and she is frustrated by the question nearly everyone asks: “Does she recognize you?”

This question is a load of BS to Taylor. Why does our culture put so much value in recognition? She suggests that recognition is something Americans greatly value, and when someone cannot recognize us we are insulted, we get hurt– so we use it as a reason to sever ties with that person. “When everyone keeps asking me, ‘Does she recognize you?’ I believe the question really is— or should be— ‘Do you, do we, recognize her? Do we grant her recognition?’”

She goes on: “Not only is it tragic, but it is wrong for a person to forget their close relations, especially family relations”

Taylor then gives examples in which friends and family members distance themselves from someone with dementia. Her mother lost all of her friends but one. Many people living with someone with dementia describe these people as “as good as dead” or “ghosts.” People with dementia therefore experience a “social death;” after all, who wants to socialize with the living dead?

One man said living with his wife who had dementia was like being with the “living dead.” When he wanted to leave the house, he left her tied up to the toilet.

People are offended when their loved one can’t remember their name, their relationship, what year it is, so they grill them with questions and always correct them by giving them the correct date, the correct name, the correct relationship– and this all just leads to confusion, frustration, anger, and sadness for both parties. Why does it matter so much what year it is now? What’s the point of correcting people with dementia?

We construct our lives out of memories. We place too much value in telling stories about the past, and don’t focus enough on the underlying social benefits of story-telling, of human interaction.

Taylor pleas for a more open-minded approach to socializing with and caring for those with dementia. She acknowledges her mother had a fairly easy decline into dementia, and that many have it worse, but many people experience dementia in the same way as her mother– at least at one point or another.

If you open your mind and spend less time on specific facts, you might start to realize that even though your mother, your father, or your friend cannot call you by name, they might still recognize you in a different kind of way.

“My mother would certainly fail a pop quiz about my name, but she lights up when she sees me,” Taylor explains. She says later in her piece:

“Our conversations go nowhere, but it hardly matters what we say…. The exchange itself is the point. Mom and I are playing catch with expressions, including touches, smiles, and gestures as well as words, lobbing them back and forth to each other in slow easy underhand arcs.”

You don’t need to know someone’s name to appreciate their company and to value them. You don’t even need to know your relationship with them. What matters is that people with dementia still value and want human interaction, and that they make an effort to have some sort of social exchange– just not in the typical way.

Taylor quotes another poignant example:

Even when speech is incoherent and void of linguistic meaning, in face-to-face interaction there is a smooth and appropriate alternating pattern of vocalizing, as well as gesticulating, back and forth. With the utterance of only “Bah,” “Shah,” “Brrrr!” and “Bupalupah,” Abe and Anna were able to communicate without any recourse to intellectual interpretation. There was a fittingness and a meaningful relationship between the rise and fall of their pitch, their pauses, and their postural shifts. … What this example illustrates is Merleau-Ponty’s argument that communication dwells in corporeality or, more specifically, in the body’s capability to gesture. [Kontos 2006:207]

This post is starting to get a bit long, so I’ll wrap it up with one last point: we don’t live enough in the moment, but people with dementia have to. Taylor talks about how she gained a newfound appreciation for living in the moment from her mother. When you can’t discuss memories with a person, you focus on the now, on the interaction– on the blue of the sky and the cuteness of a puppy. You hold hands because it’s nice and you don’t care about social norms anymore. You find happiness in the present because you literally cannot live in the past.

Perhaps if people weren’t so scared of no longer being recognized, or if we didn’t put so much value in social status and relationships with another person, we would be better able to care for those we love when they start to experience dementia. Then maybe people with dementia wouldn’t be abandoned by friends and family. And then maybe there wouldn’t be so much fear concerning dementia, which could probably help a lot of people live a little better in the present.